| Study Protocol, Biomed Biopharm Res., 2023; 20(1):136-149 doi: 10.19277/bbr.20.1.314; PDF version [+]; Portuguese html [PT] |

Impact of controlled pharmacist communication-based interventions on patient adherence to antibiotics: a protocol of a systematic review

Carla Pires ![]() ✉️

✉️

CBIOS - Center for Biosciences & Health Technologies, Universidade Lusófona de Humanidades e Tecnologias, Lisboa, Portugal

Abstract

Community and hospital pharmacists are prepared to educate or involve patients in specific interventions/programs aiming at improving antibiotic adherence. Importantly, improved antibiotic adherence is associated with the reduction of the risk of antibiotic resistance. Pharmacist communication-based interventions to improve patients’ antibiotic adherence are diverse, such as interviews, education/counselling, the provision of written information or workshops, knowledge assessment, among others. Thus, a protocol of a systematic review to evaluate the impact of pharmacist communication-based interventions on patients’ adherence to antibiotics is presented. The PRISMA-P (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for systematic review protocols) was applied. The detailed project of the present systematic review is already published in Registry Services – Open Science Framework (OSF). The confirmation of a positive impact of communication-based interventions on patients’ antibiotic adherence in community or hospital pharmacies is expected.

Keywords: pharmacy, antibiotics patient adherence, communication-based interventions, protocol

To Cite: Pires, C. (2023) Impact of controlled pharmacist communication-based interventions on patient adherence to antibiotics: a protocol of a systematic review. Biomedical and Biopharmaceutical Research, 20(1), 136-149.

Correspondence to:

Received 17/05/2023; Accepted 05/07/2023

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance occurs when patients’ infections do not respond to treatment with medicines, such as antibiotics, antivirals, antiprotozoals or antifungals. Antimicrobial resistances are likely to increase in the next decades, which can result in increased difficulty in the treatment of patients, spread of infections, development of severe illness and death. Antimicrobial resistance is one of the main global public health threats, responsible for millions of deaths, the worsening of infirmities and/or increased costs for the national health systems worldwide. Escherichia coli, Salmonella, and Pneumococcus are among the emergent resistant bacteria (1).

The inappropriate use of antimicrobial medicines may lead to resistances, because of incorrect selection, inadequate dosing, or poor patient adherence. Therefore, patient adherence to antibiotics is among the determinant factors to avoid antimicrobial resistance, i.e., taking the antibiotic in the correct dose, at the right time and for the prescribed period (2).

Pharmacists are required (i) to dispense the prescribed antimicrobials, (ii) to ensure the patients' comprehension regarding the dosage, frequency and duration of treatment, (iii) to actively participate in the disposal of unused antibiotics, (iv) to report adverse drug reactions, (v) to provide information and clarify doubts about the precautions, contraindications and interactions of antimicrobials, or (vi) to participate in public health programs/campaigns about the rational use of antibiotics (3). However, according to the results the systematic review of Lambert et al. (2022): “adherence to antibiotics did not significantly increase after pharmacist-led interventions” (4).

Thus, the primary and secondary objectives as well as the research questions of the present systematic review are, as follows:

- To evaluate the impact of pharmacist communication-based interventions on patients’ adherence to antibiotics (primary objective).

- To identify different types of pharmacist communication-based interventions to improve antibiotic adherence (secondary objective).

- To identify the most effective pharmacist communication-based interventions, which improve patients’ antibiotic adherence (secondary objective).

Primary and secondary research questions

- What is the impact of pharmacist communication-based interventions on patients’ adherence to antibiotics? (primary research question)

- What were the types of pharmacist communication-based to improve antibiotic adherence? (secondary research question)

- What were the most effective pharmacist communication-based interventions to improve antibiotic adherence? (secondary research question)

Materials and Methods

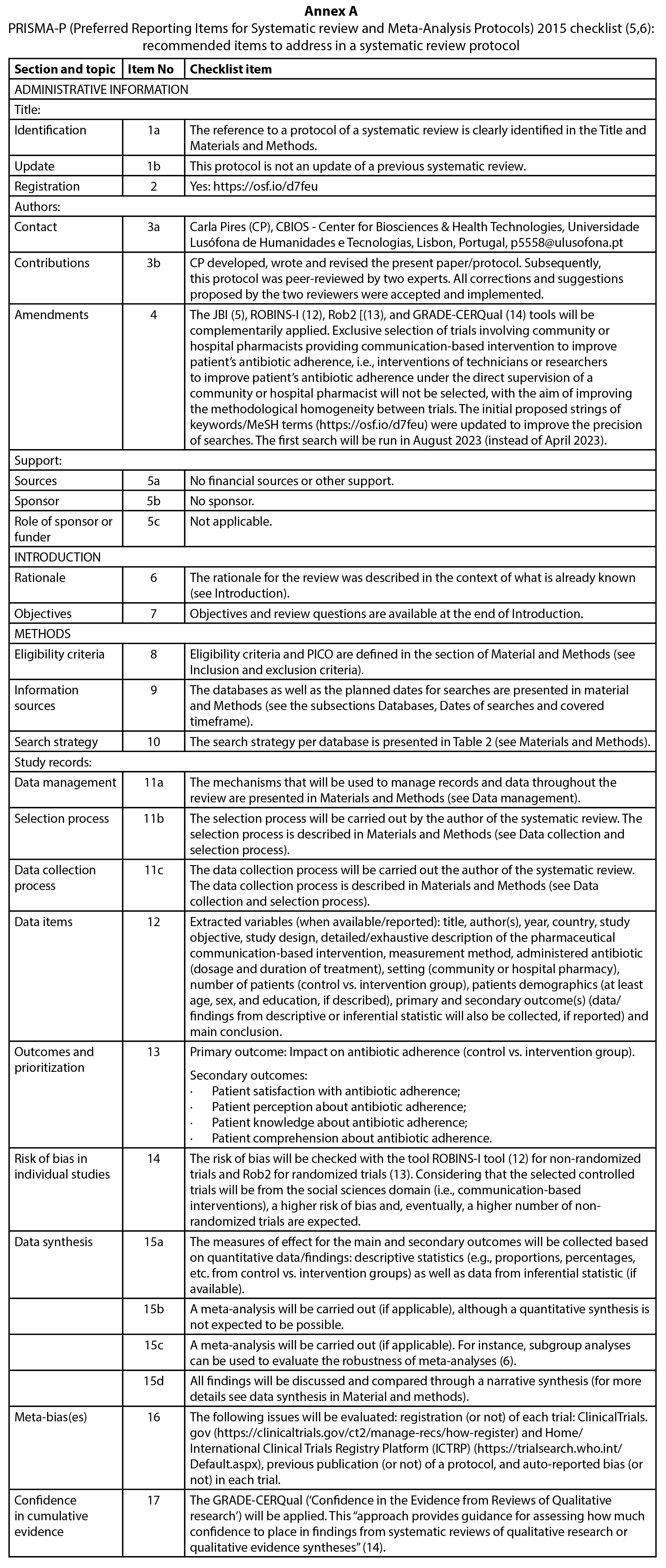

The present protocol was developed according to PRISMA-P (5,6). PRISMA-P checklist applied to the present protocol can be consulted in Annex A.

Type of review and registration protocol

The present systematic review will be conducted according to the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidance and reported according to PRISMA checklist and flow diagram (7,8). The detailed protocol of the present systematic review is registered in OSF Registries (The open registries network) (9).

PICO

The Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO) framework is presented in Table 1. PICO was applied to support the formulation of objectives, research questions as well as the literature review (5,6).

| Table 1 - PICO framework applied to the present protocol |

|

Intervention

Intervention: any pharmacist communication-based intervention provided to patients aiming at specifically improving the antibiotic adherence (e.g., patient counselling/education, interviews, workshops, provision of written information, or other).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria: patients taking an antibiotic enrolled in a controlled trial (control group vs. communication-based pharmacist intervention group). This controlled trial must be carried out in a community or hospital pharmacy, aiming to evaluate the impact of pharmacist communication-based intervention on patients’ antibiotic adherence. Only original and peer-reviewed papers will be included (without time limitations). Exclusion criteria: published papers not written in English, Spanish, Portuguese, French or Italian. Commentaries, reviews, qualitative studies, abstracts, letters to editor, and preprints and interventions conducted by technicians or researchers under the direct supervision of a hospital or community pharmacist will also be excluded.

Databases, Keywords, and MeSH terms

The screened keywords and/or MeSH terms, including their descriptors, respective strings, and search strategy per each screened database are presented in Table 2.

| Table 2 - Search strategy for each database |

|

Broad keywords were intentionally selected to ensure the likely identification of more controlled trials, considering that in a previously published systematic review related to the present topic, only 9 trials on patients’ adhesion of antibiotics were selected (4). MeSH terms (e.g., “patient compliance” and “patient adherence”) and synonyms of keywords were screened and used complementary to the search strategy purposed in the initial protocol (9). A more specific search wil be conducted in Google Scholar to refine the displayed findings.

Dates of searches and covered timeframe

Predictably, the first search is predicted to be carried out in August 2023. A final search will be run to update data. All searches will be conducted without time limit.

Selection process and data collection

Selection process and data collection will be carried out, as follows (steps 1 to 4):

- First step: after searching the keywords per each database: the title and abstract will be read: (i) papers selected based on title and abstract will be archived, and (ii) the full version of the remaining papers will be consulted before validating their exclusion/inclusion. Motives of exclusion will be annotated.

- Second step: all selected papers will be reassessed to validate paper inclusion or exclusion. Motives of exclusion will be annotated.

- Third step: extraction of data.

- Fourth step: repetition of steps 1 to 3.

Data management and collected variables

Data will be collected by the study author in a Tabular format. All data will be double-checked. PDFs of all searches will be archived. The planned extracted variables are described in the item 12 of the PRISMA-P tool (Annex A).

Data synthesis

A meta-analysis will be carried out (if applicable), although a quantitative synthesis is not expected to be possible. In order to conduct a meta-analysis, the selected studies need to be sufficiently homogeneous in terms of design and comparadors (6). However, some measures of effect for the main and secondary outcomes will be collected, such as quantitative data/findings: descriptive statistics (e.g., proportions, percentages, etc. from control vs. intervention groups) as well as data from inferential statistic (if available). Study findings will be discussed and compared through a narrative synthesis. The narrative synthesis will be based on all collected variables (see data items in point 12 of PRISMA-P) (Annex A). A summary of all selected studies will be prepared in a tabular format.

Quality assessment of the selected studies

Two tools will be applied to evaluate the quality of the selected studies, as follows: (i) The National Heart, Lung, and Blood institute (NHLBI) quality assessment tool for Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies (10) and the (ii) The LEGEND Appraisal Form for randomized controlled trials (RCT) and controlled clinical trial (CCT) (11). Both tools support the identification of eventual methodological limitations, which is in line with the requisites of item 17 of PRISMA-P (Annex A).

Risk of bias, meta-bias(es) and confidence in cumulative evidence

The adopted methodologies for assessing eventual bias, meta-bias(es) and confidence in cumulative evidence can be respectively consulted in items 14, 16 and 17 of PRISMA-P (Annex A). Particularly, the risk of bias will respectively be evaluated with the ROBINS-I tool (12) for non-randomized trials and Rob2 for randomized trials (13).

It is important to note that GRADE-CERQual (for qualitative studies) (14) was adopted for evaluating the confidence in cumulative evidence rather than GRADE (for quantitative studies), because diverse limitations in the application of GRADE (15,16) were previously anticipated.

Results and Discussion

The results of the present systematic review are expected to be published until the end of 2023 or first trimester of 2024. Findings will be discussed and compared through a narrative synthesis, although some descriptive statistics can be applied to quantify some variables (e.g., proportion of female/male participants; % of participants per education degree, average, and standard deviation of the number of participants, etc.). Additionally, a high risk of bias of the selected studies is anticipated, since the selected controlled trials were designed to evaluate pharmacist communication-based interventions (i.e., studies from social sciences, necessarily associated with a certain degree of methodological heterogeneity and subjectivity).

Overall, an impact (positive or negative) of pharmacist communication-based interventions on patient adherence to antibiotics in community or hospital pharmacies is expected in this systematic review, because the findings of previous similar/related studies are not consensual (with some studies detecting negative (4,17) or positive (18) results)).

Only one systematic review related to the present topic has been identified, which was conducted by Lambert et al. (2022) (4). It should be noted that from the 17 selected studies in this systematic review, patient adherence to antibiotics was reported in only 12 out of these 17 studies as a secondary outcome, with only 9 studies complying with the inclusion criteria of the present systematic review. These 9 studies will be included in the present work (if not identified by the proposed search methodology). The findings from this systematic review were somewhat unexpected, i.e., the “adherence to antibiotics did not significantly increase after pharmacist-led interventions” (4), although this conclusion was based on a restricted number of studies. For instance, differences in patient adherence to antibiotics were also not found between the intervention and control groups in the trial of Göktay (2013) (17), in opposition to the findings of Gotsch (1982), with increased adherence in the intervention group (18). Both controlled trials were based on a pharmacist communication-based intervention (17,18).

Study Limitations

Data collection and analysis will be carried by just one author, which could lead to eventual selection and/or analysis biases. However, all results will be double-checked. For instance, two tools will be applied to assess the quality of the selected articles (10,11). The number of selected databases and keywords may have been limited, although the use of Google Scholar and the selection of studies without time limitations will predictably enhance the capture of more results.

Conclusion

In this work, a preliminary protocol of a systematic review on the impact of controlled pharmacist communication-based interventions on patient adherence to antibiotics is presented.

Author contributions statement

This protocol was entirely conceived, designed and written by CP. In addition, this protocol has been peer-reviewed by experts in the field and has been updated according to their suggestions and corrections.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgements

The author expresses her thanks to CBIOS - Research Center for Biosciences and Health Technologies, Universidade Lusófona de Humanidades e Tecnologias, Lisbon, Portugal.

Conflict of Interests

The author declares that there are no financial and/or personal relationships that could represent a potential conflict of interest

References

1. World Health Organization (WHO), Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE). (2021). Antimicrobial resistance and the United Nations Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework: guidance for United Nations country teams. ISBN (WHO) 978-92-4-003602-4 (electronic version).

2. Prestinaci, F., Pezzotti, P., & Pantosti, A. (2015). Antimicrobial resistance: a global multifaceted phenomenon. Pathogens and global health, 109(7), 309–318. https://doi.org/10.1179/2047773215Y.0000000030

3.European Commission. (2017). EU Guidelines for the prudent use of antimicrobials in human health (2017/C 212/01). Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52017XC0701(01)&from=ET (accessed on 4-5-2023).

4. Lambert, M., Smit, C. C. H., De Vos, S., Benko, R., Llor, C., Paget, W. J., Briant, K., Pont, L., Van Dijk, L., & Taxis, K. (2022). A systematic literature review and meta-analysis of community pharmacist-led interventions to optimise the use of antibiotics. British journal of clinical pharmacology, 88(6), 2617–2641. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.15254

5. Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., Stewart, L. A., & PRISMA-P Group (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic reviews, 4(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

6. Shamseer, L., Moher, D., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., Stewart, L. A., & PRISMA-P Group (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 350, g7647. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7647

7. Aromataris, E., & Munn, Z. (Editors). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI, 2020. Available at: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-01

8. PRISMA. (2023). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist and flow diagram. Available at: http://prisma-statement.org/prismastatement/flowdiagram.aspx (acedido em 13-5-2023).

9, Pires, C. (2023). Impact of controlled pharmaceutical communication-based interventions on patient adherence to antibiotics: a systematic review, May 2023. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/D7FEU

10. NHLBI. (2021), The National Heart, Lung, and Blood institute (NHLBI) quality assessment tool for Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies. Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 13-5-2023).

11. Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center. Evidence Evaluation Tools & Resources (LEGEND). Available at: https://www.cincinnatichildrens.org/research/divisions/j/anderson-center/evidence-based-care/legend (acedido em 13-5-2023).

12. Sterne, J.A.C., Hernán, M.A., McAleenan, A., Reeves, B.C., & Higgins, J.P.T. Chapter 25: Assessing risk of bias in a non-randomized study. In: Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M,, Li, T., Page, M.J., & Welch, V.A. (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3 (updated February 2022). Cochrane, 2022. Available at: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

13. Higgins, J.P.T., Savović, J., Page, M.J., Elbers, R.G., & Sterne, J.A.C. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In: Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., & Welch, V.A. (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3 (updated February 2022). Cochrane, 2022. Available at: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

14. Lewin, S., Booth, A., Glenton, C., Munthe-Kaas, H., Rashidian, A., Wainwright, M., Bohren, M. A., Tunçalp, Ö., Colvin, C. J., Garside, R., Carlsen, B., Langlois, E. V., & Noyes, J. (2018). Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: introduction to the series. Implementation science : IS, 13(Suppl 1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0688-3

15. Berkman, N.D., Lohr, K.N., Ansari, M., et al. Grading the Strength of a Body of Evidence When Assessing Health Care Interventions for the Effective Health Care Program of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: An Update. 2013 Nov 18. In: Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK174881/

16. Granholm, A., Alhazzani, W., & Møller, M. H. (2019). Use of the GRADE approach in systematic reviews and guidelines. British journal of anaesthesia, 123(5), 554–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2019.08.015.

17. Göktay, N.B., Telefoncu, S., Kadioǧlu, S.B., et al. (2013). The role of patient education in adherence to antibiotic therapy in primary care. Marmara Pharmaceutical Journal, 17, 113‐119.

18. Gotsch, A.R.A., & Liguori, S. (1982). Knowledge, attitude, and compliance dimensions of antibiotic therapy with PPIs: a community pharmacy‐based study. Medical care, 20(6), 581–595. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-198206000-00004

|