| Original Article, Biomed Biopharm Res., 2022; 19(1):3-18 doi: 10.19277/bbr.19.1.274; pdf version [+] ; Portuguese html version [PT] |

Exploratory Study on Municipalization of Health in Angola – Characterization of Human Resources for Health staffing and Health Units’ managers’ profile in Healthcare services and Training institutions of Cabinda Province

Teresa Macosso 1, Alberto Macosso 2,a, Maria do Céu Costa 1,*, João Gregório 1,*,⸸

1 CBIOS - Universidade Lusófona’s Research Center for Biosciences & Health Technologies, Campo Grande 376, 1749-024 Lisboa, Portugal, 2MINSA - Ministério da Saúde de Angola

a MINSA, retired

* shared senior mentorship

⸸ corresponding author:

Abstract

In Angola, the scarcity of human resources for health (HRH) is well known. Lately, there has been a focus on education and professional training structures, as well as the necessary profile of health units’ managers. The general objective of this study was to describe the perceptions of HRH Managers of Primary Health units of Cabinda Province about HRH training and retention. A cross-sectional observational study was performed, with semi-structured interviews supported by a survey, followed by a focus group, addressed at a convenience sample of HRH and Health Units managers in the province of Cabinda. 10 health units participated, where 13 managers were interviewed. As for the HRH profile, there is a majority of nurses, with a ratio of nurses to physicians of 8.6:1. As for the profile of managers, only three are postgraduate technicians in management. Training schools’ output in the previous year was 746 senior and middle technicians. Managers cited two main areas of improvement as essential to address the HRH imbalances in Cabinda: "Leadership empowerment" and "Improving information system efficiency". Opportunities were identified to improve the training of Health students, retention of HRH and managers of Health and training units in Cabinda. The definition of policies for HRH in Cabinda should focus on improving health teaching and management conditions with a special focus on empowerment of leaderships, and reinforcing the use of management tools and information systems. Desirably, implementing Management, Control and Quality Assurance Systems.

Keywords: Health Workforce; Quality of Health Care; Health Management; Angola

Recebido: 11/11/2021; Aceite: 13/03/2022

Introduction

The training of health professionals is strategic to strengthen health systems, especially in countries where Human Resources for Health (HRH) are lacking (1). In recent years, several studies have been carried out to characterize and identify the main challenges faced by institutions that train health professionals around the world, and particularly in sub-Saharan Africa (1–3). However, in African Portuguese Speaking Countries (PALOP) this research has only addressed medical training (4). Albeit issues such as training and retention strategies have been present in the research agenda for some time, understanding the role of HRH management in these low-resource settings is a recent approach for policy-makers.

Human Resources for Health are universally recognized as a priority in health systems. This importance has led to several initiatives at the World Health Assembly and at the African Regional Assembly (5,6). These include the 2001 Abuja Declaration (7), which committed governments in the Region to increase financial resources for health including HRH; the 2008 Ouagadougou Declaration (8), on Primary Health Care (PHC) and Health Systems, which identified HRH as a priority for health; and the Luanda Resolution (9) are among the most relevant.

Angola is among the countries where this shortage of health professionals is most felt, across all provinces (10). The province of Cabinda has been a laboratory for studies on organizational, political and practical issues resulting from Angola’s HRH strategy. The health system in the province of Cabinda is structured according to the National Health System of Angola (SNSA) (11). The SNSA is structured as follows: i) public subsystem that includes the National Health Service (SNS), Health Services of the Armed Forces and the National Police and also health units linked to public companies; ii) private subsystem that includes philanthropic and profitable health units. The SNS is structured in three levels of care: i) primary or level I, composed of Type I and II Health Posts, Health Centers, Reference Health Centers and Municipal Hospitals; ii) secondary level, the General or Provincial Hospitals and iii) tertiary level, the Central Hospitals (12). Regarding health management, health services provided to the population of the province depend on the Provincial Health Secretariat, which is a governmental body with administrative subordination to the Provincial Governor and technical subordination to the Minister of Health. In the municipalities, health services are managed by the Municipal Health Secretariats, with technical subordination to the Provincial Health Secretary and administrative subordination to the Municipal Administrator (11,12).

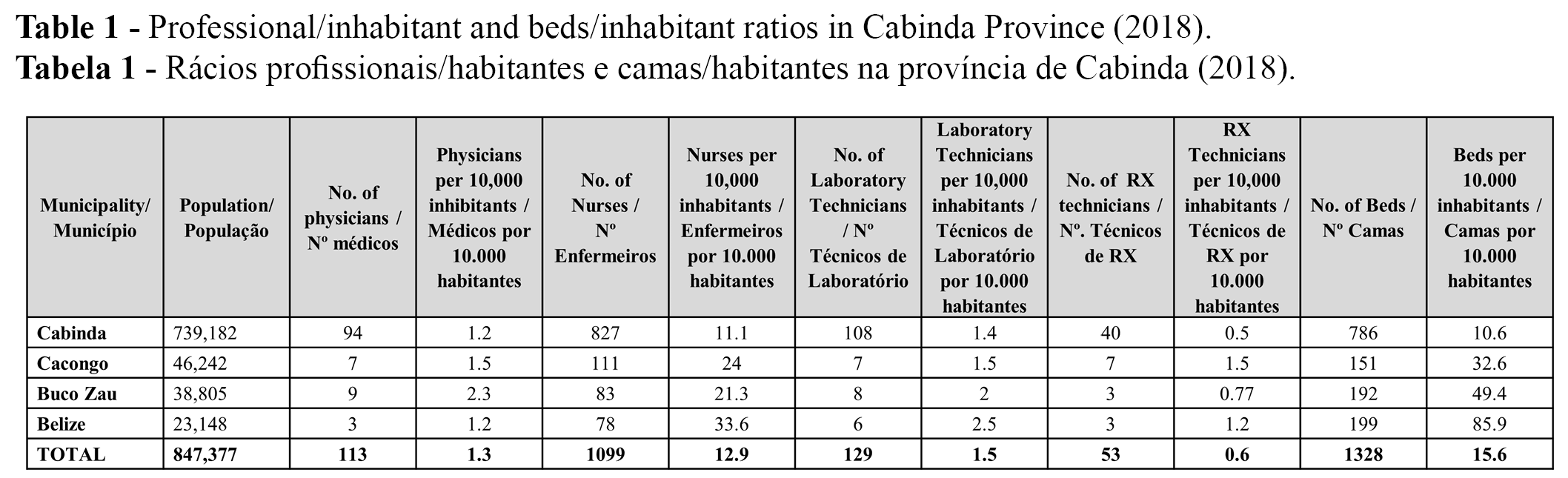

Angola's National Health System (SNS) has faced a shortage of human resources in quantity and quality to meet the essential needs of the population, although some progress has been made. The precise context that affects the distribution of the health workforce and HRH management practices was assessed with data collected in 2015 and recommendations were made to improve the HRH distribution in Cabinda (10). In 2015, for every 10,000 inhabitants there is 1 physician, 16 nurses, 3 diagnostic and therapeutic technicians, 5 hospital support workers, 11 general workers and 3 health promoters (13). A number still far below ideal to meet the needs of the population (10). In 2019, the number of physicians per 10,000 inhabitants has increased to 2.3 but the number of nurses has remained more stable, at 16.5 per 10,000 inhabitants (14). Macaia and Lapão (15), described a poor distribution of HRH in Cabinda, with geographical imbalances that benefit the urban areas of Cabinda province. The most recent data on professional/inhabitant ratios and beds/inhabitants in the Province of Cabinda is shown in Table 1 (16,17), presenting a slightly better situation than the country's total in 2014/2015 (18), particularly on the distribution of physicians in the province of Cabinda.

In order to face the shortage of HRH, several strategies may exist, among them, the increase in the availability of undergraduate courses for health professionals in the areas in need (19). Fronteira et al. (4) identified the existence of several undergraduate and graduate programs in health at the faculties of Angola, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique. In these countries, one of the main reasons for the shortage of physicians is the limited training capacity of medical schools, due to the high number of candidates for a limited number of places, low graduation rates, lack of infrastructure, labor, poorly qualified teaching staff and dependence on foreign teachers, low teacher salaries, and insufficient infrastructure, among other reasons (4). Macaia and Lapão (15) previously highlighted a significant fluctuation over the years in the number of HRH available, depending on recruitment standards and international cooperation for physicians, and other factors of recruitment and fixation for the remaining professionals. However, the specific training needs of these professionals were not determined.

In the conception of the National Health Development Plan (2012-2025) (10), the deficit of qualified human resources in all areas of the National Health Service in Angola was identified as one of the risk factors for its sustainability. For this reason, the following strageties were defined within in the HRH Management Program, among others: i) improvement in management and planning, ii) reinforcement of skills in the areas of management and planning, iii) improvement in the distribution and establishment of HRH, iv) improvement of the mechanisms and instruments of initial training and v) improvement of continuous training. The level of incentives, wages, and unattractive working conditions were noted as risk factors of the program.

Considering that for any Health System the quality of care is sustained in the definition of the number and qualification of HRH, it is important to investigate, according to the strategies, objectives, and goals recommended in the PNDS of Angola: i) What HRH profile is necessary? ii) What conditions of graduate and postgraduate/continuous training exist to satisfy this profile? iii) What are the characteristics of HRH management at the service level, taking into account the manager's profile, planning, administration, and development? A research project is in progress to contribute to the body of knowledge necessary to answer these questions. The exploratory study presented here is the initiation of the project and intends to describe the perceptions of HRH Managers of Primary Health units of Cabinda Province regarding HRH training and retention policies, while trying to understand if any significant evolution on HRH retention was made in the 2015- 2018 triennium in order to produce specific recommendations for policy-makers.

Materials and Methods

To pursue the objective of this study, we opted for a cross-sectional observational study, based on semi-structured interviews supported by a survey containing closed and open questions, followed by a focus group. This questionnaire was applied during the month of May 2018, in a convenience sample of Principal Managers (General Directors), HRH managers of primary care units in Cabinda Province and managers from teaching schools. Health Units were selected in both the Urban, Suburban and Rural areas, thus allowing an image closer to the reality of the whole province of Cabinda. In this research, 10 Health Units were included for the interviews with professionals, representing about 9.8% of a total of 102 Health Units that make up the Public Health Service in Cabinda, namely one Urban Maternal-Child Centre, two Suburban Health Centers, and seven Municipal Hospitals between Rural (four), Urban (one) and Sub-Urban (two). In addition to these care units, managers from four teaching schools for health technicians (one Higher Polytechnic Institute, one School for the Training of Health Technicians, one College and one Faculty of Medicine) were interviewed. These institutions for training health technicians train professionals in different areas, in courses in medicine, nursing, laboratory, radiology, pharmacy and physiotherapy.

The questionnaire was divided into two parts. The first part aimed to identify the profile of the human resources in each center, from their qualification to the existing number and distribution among the different health units in the province. The second part aimed to identify perceptions about the quality of teaching, the quality of care provision, and the main opportunities for improvement identified by the unit managers.

Finally, a focus group with health services’ managers of the province allowed the collection of more information to identify possible solutions to address the identified issues. The objective of this focus group was to analyze and comment on the results of the survey, aiming to identify a set of policies and measures that could contribute to improve health service provision and the training and retention of health professionals in Cabinda. A focus group script was developed, and moderators were instructed to seek consensus on the priority of problems and point out the paths to a solution. Notes were taken in writing and through audio recording with the informed consent of the participants.

The statistical analysis performed was purely descriptive, according to the objectives of the study, and performed in SPSS v.22. All professionals signed an informed consent document, where they authorized the anonymous collection of their data only for the purposes of this research work.

Results

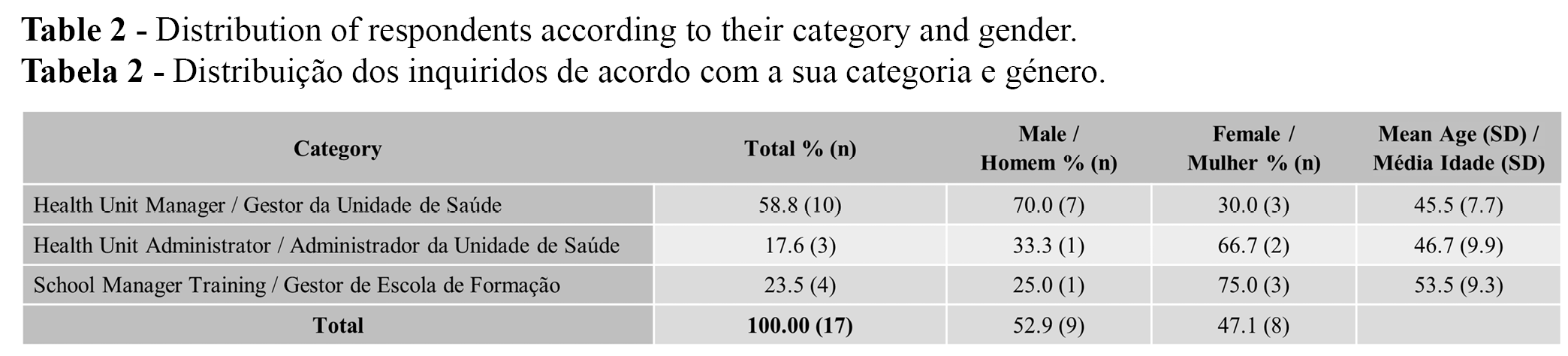

Seventeen individuals have completed the survey. Most of them were Health unit managers (Table 2). The individuals’ ages varied between 33 and 66 years old. Training school managers had the highest mean age (53.5), compared with the other professionals.

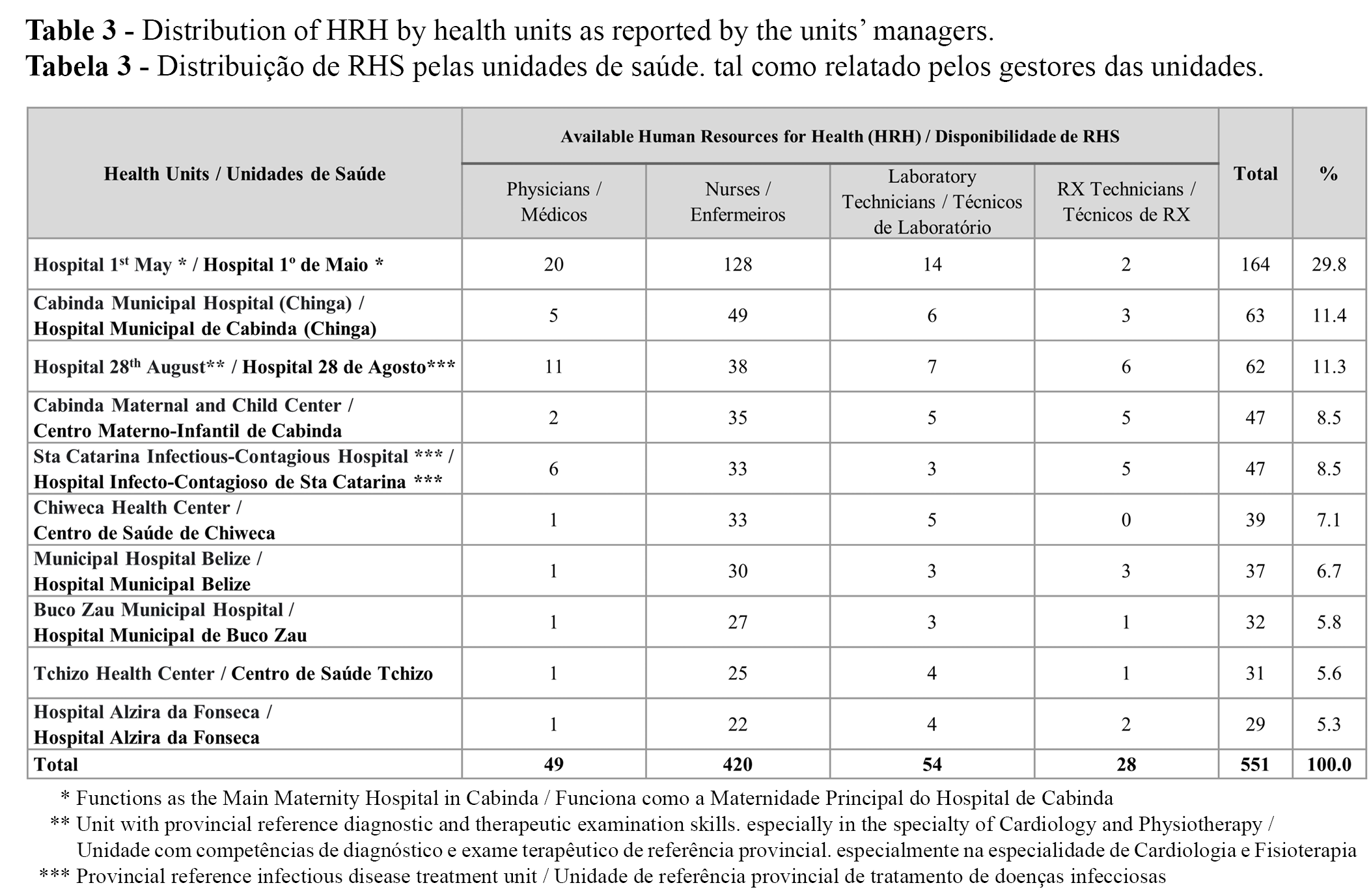

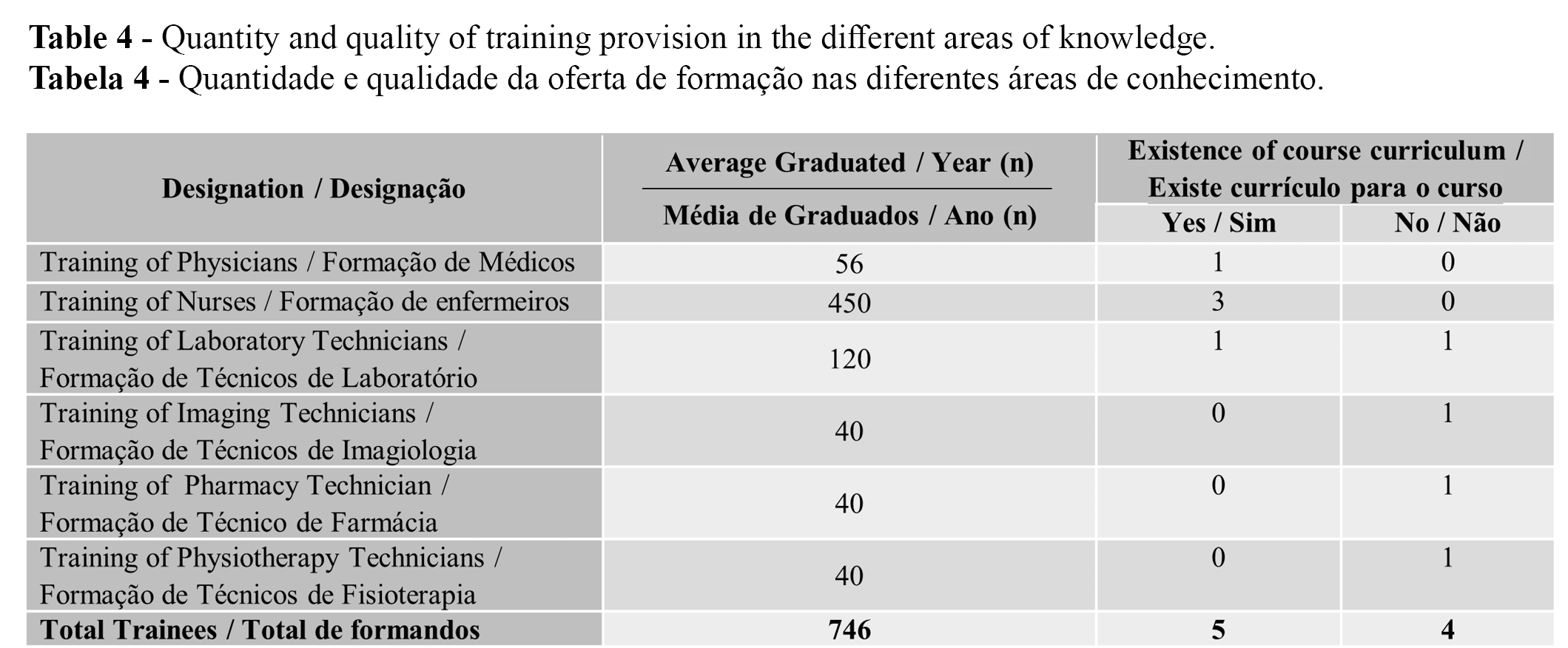

From managers’ own data collection in the ten health units, it was possible to ascertain that there were 551 qualified technicians (Table 3). Approximately 30 % of all HRH were allocated to 1st of May Hospital, which also serves as the main maternity hospital in Cabinda. Most of the HRH were nurses, with a total of 420 nurses from various specialties (76.2% of the total professionals), 82 Laboratory and X-ray technicians, and 49 physicians, in a ratio of 8.6 nurses for each physician. Regarding the training offer (Table 4), the four training schools participating in the study trained approximately 746 senior and middle level technicians in the previous year. The majority were from nursing courses (60.3%), followed by the laboratory course of Clinical Analysis/Laboratory Technicians with 120 technicians (16%), the physician’s course with 56 (7.5%) trained and, finally, the imagiology, pharmacy and physiotherapy courses that trained 40 (5.3%) technicians each, respectively. No postgraduate programs directed at these professionals were mentioned. Among the six existing courses, administered in the different training units, four work with the respective academic curricula and the remaining two do not. This means that the courses are administered without a curricular structure defined by law, depending on the experience of the professor.

In total, of the 13 health unit managers, eight (61.5%) individuals had an academic degree, three (23.1%) were post-graduate technicians in management and two (15.4%) did not mention their training. It is important to highlight that no respondent with functions that include HRH management had specific training for this purpose. As for satisfaction with the working conditions and professional career development of the manager of the healthcare unit, two (15.4%) managers reported being satisfied and 11 (84.6%) showed dissatisfaction. Regarding the HRH managements processes, only three (23.1%) managers confirmed the existence of an HRH planning document in their institution. Likewise, it was found that five (38.5%) of the managers knew of the existence of a Continuous Training Plan in the institution and the other eight (61.5%) were unaware of its existence.

During the survey, in which the Questionnaire was administered individually to each participant and completed face-to-face, a space for "Comment" after the final answer about what improvements he or she would introduce in the functioning of the unit was not filled by most respondents but allowed the collection of three spontaneous statements, transcribed (and translated) below:

“... in relation to training courses, several courses do not have elaborated and approved curricula. Each teacher administers classes according to their criteria. As for practical training in care units, there is little availability of technical and human conditions to guarantee quality training. ”

- F1, 44 years, Manager, Educational Institution

“... we have a training program defined at a higher level (Cuban model) and that is why we have mainly Cuban teachers. They administer theoretical classes at the Faculty, but do not accompany students in the practical training, either in the preventive area or in the hospital area. (…) We have already suggested to the Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Technology and Innovation, for the revision of the curricula of the courses and the integration of Angolan teachers and teacher training for nationals in order to overcome these gaps.”

- F2, 54 years, Manager, Educational Institution

“… At the hospital, we do not have the technical and material conditions for teaching. Students come for training, but there is no good coordination between the school and the hospital, so that students are more on the schedule than they actually learn. And this phenomenon is reflected in their performance, once integrated into the exercise of their profession.”

- M1, 48 years, Health Unit Manager

To discuss the survey results, all the 13 managers were invited for the focus group. The focus group addressed the main difficulties managers faced in their daily work to fulfil their activities and contribute to the HRH managing. Two main questions were put to the discussion: “What difficulties do you feel that protract the normal operation of the health unit?” and “What improvements would you make/need to the operation of the health unit?” Among the managers, there were some disagreements on which difficulties were more important. For a HRH manager, the most important difficulties were the “lack of a strategic plan, with clear goals and objectives in terms of health policies" and "Information systems with non-updated records." For a health unit manager, the more important barriers to improve the quality of services were "Health professionals' lack of interest in knowing their performance," the "Bureaucratic procedures that slow down the decision-making process" and "Health professionals with long and accommodating careers.” HR managers seem to give less importance to the excess of useless activities than the health unit managers.

To improve the function of the health care units, the managers pointed out as measures to be implemented: i) the approval of the staffing plans; ii) implementation of electronic health databases; iii) increasing the HRH salaries; iv) improvement in clinical communication; v) medication management; vi) budget improvements and vii) rehabilitation and recovery of existing facilities and equipment. Focus group participants reflected on these findings and grouped them into two main components of action for future strategic plans:

Component 1 "Leadership empowerment" - reflecting the need for managers to be empowered, both in terms of knowledge and support from the central administration (Ministry of Health)

Component 2 "Improving information system efficiency" - which reflects managers' perception of the impact of inefficient information systems on HR workload and on management quality.

Finally, the focus group proposed that the results of the discussion and the solution proposals should be analyzed in the Provincial Secretariat and, once validated, sent to the Government of Cabinda Province and the Ministry of Health, Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Technology and Innovation and the Ministry of Education of Angola. After central approval, participants referred that there should be a follow-up of the planning, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of the proposed solutions that may result in improved quality of health indicators in Cabinda Province and perhaps in the country as a whole.

Discussion

This exploratory study presents relevant data on the characterization and distribution of health professionals and managers of health units in the province of Cabinda.

Considering the distribution of health professionals, there is still a great concentration on the urban area of the province of Cabinda and on central hospitals. This observation, although not new, shows that the policies implemented to improve the distribution of professionals across the territory still have a long way to go to be considered successful. Oliveira and Artmann (20) had already identified in March 2009 the number of physicians in rural areas in Cabinda Province, with some areas with a ratio of 1 physician / + 3000 inhabitants and other locations of more than 35,000 inhabitants without medical coverage. In 2014, the province had only 47 Angolan national physicians working in public health services (18). In urban areas, covering 86.9% of the population (21), there were approximately 79% of these physicians, with the remaining 21% distributed in rural municipalities, most of them occupying management functions in health units. The same situation also occurred at the national level: in 2011, about 42% of physicians were concentrated in the country's capital Luanda, with only 24% of the total population of Angola. This urban concentration effect is also seen with other provincial capitals which concentrate around 85% of the physicians’ workforce (13). In the study published by Macaia and Lapão (15), the authors considered that this concentration shows a balance in HRH policies that, according to the authors, can be understood as a result of a centralized recruitment process that allocates HRH to all health units (via the Provincial HRH Department), as well as due to wages that are not differentiated in terms of geographic location. In addition to the high concentration of physicians in the cities, the high nurses/physicians ratio found (8.6 nurses:1 physician), reflects the lack of trained physicians that is typical in the WHO African region (22). The need to increase the training of physicians and incentives for them to work in rural areas must remain a priority in the Angolan health system.

If we consider primary health care the basis for the provision of health services and the main route of access to the health system, the professional/inhabitants deficit ratio can be a critical point for materializing the Municipalization of Services strategy. It should be noted that the estimated population that these studied units serve is around 801,374, and some units, despite being located in the main city (Cabinda), due to their specificity, meet a provincial demand (Ex. Tuberculosis, HIV / AIDS, Physiotherapy, Technical Exams Cardiology). Thus, it is complex to define the proportion of care needs in urban/suburban and rural areas.

Regarding the training offer, the training schools trained about 746 senior and middle technicians in one year (referring to 2017). These figures reveal the local capacity to carry out initial training at both the middle and higher levels is installed. However, healthcare units managers emphasize the lack of technical and technological resources, deficient tutorial teaching, and weak knowledge of theoretical and practical concepts. These deficits are evidenced by those who work in units and also, by the managers of training units, regarding the curricular quality of the courses, teacher profile, teaching support in the practical field and rigor in the evaluation of students. All these findings reflect the published evidence (4), which means that few steps have been taken or that the implemented measures have not been successful.

In the management of health care units, only three (23.1%) managers confirmed the existence of an HRH planning document. The deficit in the training of these managers may be the basis for not creating management tools and improving results. In addition, the vast majority (84.6%) are dissatisfied with working conditions. This factor can be an impediment to the good performance of the management and of the professional development of HRH. Moreover, organizational management shortcomings are still dramatically constrained by resource shortages including high absenteeism rates, lack of data recording support, and non-existent core competencies.

To improve the function of their care units, the managers point out several measures to be implemented: the approval of minimal staff requirements, increase in HRH salaries, improvement in clinical communication and medication management, budget improvements and rehabilitation and recovery of existing facilities and equipment. It should be noted that three of the main schools for the training of health professionals (HP), namely the Faculty of Medicine, the Polytechnic Institute of the Universidade 11 de Novembro and the School for the Training of Health Technicians, are relatively young (less than 10 years old). Hence, the “rehabilitation of the facilities” measure may not apply to these institutions. However, it is known that at least 50% of medical equipment in developing countries is totally or partially inoperable, for various reasons (23,24). This "facility rehabilitation" measure may thus reflect the need for better laboratory equipment and its maintenance. As health cannot be dissociated from the need for maintenance of diagnostic equipment, a priority intervention should also be the training of technicians to maintain this equipment in parallel with health technicians who will operate them.

This study is another contribution to support health policy-making in Angola. Of the 46 countries in the WHO African Region, 36 were considered to be HRH crisis countries. Of these, 10, including Angola, were considered to have a critical HRH deficit; 24 had no national HRH policy; 34 had no strategic plan for their HRH; and 35 had no HRH observatory. The Luanda Resolution left member states with the challenge of approving their HRH policies and strategies by 2014 (9). In Angola, the most recent National Health Development Plan 2012-2025 (PNDS), a long-term strategic-operational instrument (10), is intended to materialize the guidelines set forth in the "Angola 2025" Development Strategy and the National Health Policy, within the framework of the National Health System reform. However, despite the work done over the last decade, the Angolan government recognizes that the main constraints in the area of human resources still exist. These include the serious lack of information for managing and administering the health workforce at all levels, workplaces where, due to their geographic location or isolation, it is difficult to locate health technicians and a strong dependence on expatriate technicians, particularly for specialized cadres. This implies an urgent need to know how many HRH exist, where they are, what they do and how they do it. It is not unconnected to these constraints that the amount of the Angolan State Budget allocated to the health sector is 5.65% of GDP (25), still far from the 15% established as a goal in the commitment of the African Union Heads of State Declaration in Abuja (7).

In their inferential study, Macaia and Lapão (15) considered that there was a balance in HRH policies. This balance could be understood as a result of the centralized recruitment process (through the Provincial HRH Department) for the public services that assign HRH to all health facilities, as well as the salaries, that were not differentiated in terms of geographic location. Moreover, according to these authors' findings, this reality needs to be better understood and policies need to be defined to address it. As we can see with the present study, this balance is not yet settled. The processes of erosion and non-fixation of HRH continue, in good part not for lack of policies, but due to the lack of implementation of policies already defined in the law. One example is the lack of implementation of Presidential Decree 260/10 (26), which approves the Legal Regime of Hospital Management defining the rules of structuring, coordination, organization and operation of central hospitals, general hospitals, municipal hospitals and special establishments and services throughout the Angolan territory.

Evidence of the need to implement Human resources management practices in Sub-Saharan African countries to mitigate the impact of an inadequate health workforce on the burden of disease is long-standing (27). However, the solutions are not always linear and the importance of context must be underlined (28). In the context of Cabinda, the geographical location and the distance to the central government in Luanda may contribute to the lack of developments in the last years. Moreover, human resources managers in Cabinda, besides the lack of institutional support they mention that is rooted in their context, seem to emphasize the need to update the information systems, both clinical and managerial, to increase their efficiency. Health information systems (HIS) are one of the six essential blocks of and health system (29). Our findings support the belief that little has been done in strengthening this aspect of the Angolan health system, although its importance is recognized in the latest national health plan (10). However, the focus of current HIS has been on epidemiological surveillance. It is therefore suggested that more importance should be placed in the implementation of appropriate health information systems with the necessary training of human resources managers, specifically focused on managerial duties and quality improvement, in future national health plans.

This work has some limitations that should be acknowledged. The choice of a convenience sample of managers may have biased the sample towards people more willing to participate and partake in some form of discussion that, in their perspective, could influence policy makers to intervene. This could be avoided by selecting a random sample among the 109 health units, but we considered this option unfeasible. In addition, other methodologies such as a Delphi panel with key opinion leaders selected in the province of Cabinda could have been used to perform this study. Nevertheless, we consider that our choice was the most feasible and the least prone to bias possible in the current context.

Conclusion

This study affirms that health units’ managers have little institutional support to define policies for human resources for health, as evidenced by the absence of a development plan for human resources. Improving the information systems and communication between central planners and provincial authorities seems to be a priority. There is a valuable mission commitment although managers with specific training do not prevail; for this reason, the deficit in the creation of management tools, both strategic and operational, can be justified, with emphasis on staff and adequate staff planning due to lack of knowledge of organic needs and their deficits, continuous training plans for the training of employees, and consequent career development. Therefore, we believe more focused studies are needed to identify restraining and facilitator factors that may contribute to the improvement of HRH managers’ skills and teaching quality of health professionals in general within Cabinda province.

Authors Contributions Statement

MC and JG, conceptualization and study design; TM and AM, experimental implementation; TM, AM, MC, and JG, data analysis; TM, MC and JG, drafting, editing and reviewing; TM, tables; MC and JG, supervision and final writing.

Funding

This study was funded by national funds through FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., under the UIDB/04567/2020 and UIDP/ 04567/2020 projects. João Gregório is funded by Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) Scientific Employment Stimulus contract with the reference number CEEC/CBIOS/EPH/2018.

Acknowledgments

We express our thanks to the institutions: University Lusófona for hosting the research project that resulted in this study; Cabinda Provincial Government for the authorization to conduct research in its administrative jurisdiction; to the heads of the health units targeted for research at the level of the Cabinda Province; to University 11 de Novembro in Cabinda, for their collaboration on the research project underlying this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no relationship of potential conflict of interest.

References

- Mullan, F., Frehywot, S., Omaswa, F., Sewankambo, N., Talib, Z., Chen, C., Kiarie, J., & Kiguli-Malwadde, E. (2012). The Medical Education Partnership Initiative: PEPFAR’s Effort To Boost Health Worker Education To Strengthen Health Systems. Health Affairs, 31(7), 1561–1572. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0219

- Chen, C., Buch, E., Wassermann, T., Frehywot, S., Mullan, F., Omaswa, F., Greysen, S. R., Kolars, J. C., Dovlo, D., El Gali Abu Bakr, D. E., Haileamlak, A., Koumare, A. K., & Olapade-Olaopa, E. O. (2012). A survey of Sub-Saharan African medical schools. Human Resources for Health, 10(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-10-4

- Mullan, F., Frehywot, S., Omaswa, F., Buch, E., Chen, C., Greysen, S. R., Wassermann, T., ElDin ElGaili Abubakr, D., Awases, M., Boelen, C., Diomande, M. J.-M. I., Dovlo, D., Ferro, J., Haileamlak, A., Iputo, J., Jacobs, M., Koumaré, A. K., Mipando, M., Monekosso, G. L., … Neusy, A.-J. (2011). Medical schools in sub-Saharan Africa. The Lancet, 377(9771), 1113–1121. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61961-7

- Fronteira, I., Sidat, M., Fresta, M., Sambo, M. do R., Belo, C., Kahuli, C., Rodrigues, M. A., & Ferrinho, P. (2014). The rise of medical training in Portuguese speaking African countries. Human Resources for Health, 12(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-12-63

- WHO. (2009). Resolution WHA59.23 on rapid scaling up of health workforce production, 2006; Resolution WHA59.27 Strengthening Nursing and Midwifery, 2006. WHO Regional Committee for Africa.

- WHO. (2010b). Resolution WHA63.16: WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel.

- The Abuja Declaration and the plan of action : an extract from the African Summit on Roll Back Marlaria, Abuja, 25 April 2000 (WHO/CDS/RBM/2000.17)., (2000). https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/67816

- Ouagadougou declaration on primary health care and health systems in africa: Achieving better health for Africa in the new millennium. (2008). International Conference on Primary Health Care and Health Systems in Africa.

- Regional Committee for Africa. (2012). Road map for scaling up the human resources for health for improved health service delivery in the African Region 2012–2025 (Document AFR/RC62/7).https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259617

- MINSA. (2014). Plano Nacional de Desenvolvimento Sanitário 2012-2025.

- 11. Lei de Base do Sistema Nacional de Saúde, (1992) (testimony of Decreto Presidencial Lei n° 21-B/92 de 28 de Agosto).

- Regulamento Geral das Unidades Sanitárias do Serviço Nacional de Saúde, (2003) (testimony of Decreto no54/03 de 5 de Agosto.).

- Costa, A., & Freitas, H. (2014). Recursos Humanos da Saúde em Angola: Ponto de situação, evolução e desafios. (Documento de referência para a elaboração do PDRH 2013-2025).

- WHO. (2019). Contribuindo para a melhoria da Saúde em Angola - Relatório bianual 2018-2019.

- Macaia, D., & Lapão, L. V. (2017). The current situation of human resources for health in the province of Cabinda in Angola: is it a limitation to provide universal access to healthcare? Human Resources for Health, 15(1), 88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-017-0255-7

- MINSA. (2020). Relatório do Governo Provincial de Cabinda , I Trimestre 2020.

- Secretaria Provincial da Saúde. (2018). Relatório Diagnóstico da Secretaria de Cabinda 2018.

- Secretaria Provincial da Saúde. (2015). Relatório da Secretaria provincial da Saúde de Cabinda. Ano 2014.

- Dussault, G., & Franceschini, M. C. (2006). Not enough there, too many here: understanding geographical imbalances in the distribution of the health workforce. Human Resources for Health, 4(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-4-12

- Oliveira, M. dos S. de, & Artmann, E. (2009). Características da força de trabalho médica na Província de Cabinda, Angola. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-311x2009000300009

- INE. (2014). Resultados Preliminares do Recenseamento Geral da População e Habitação.

- World Health Organization. (2006). Working together for Health: World Health Report 2006. In World Health.

- Issakov, A. (1994). Health care equipment: a WHO perspective. In C. Van Gruting (Ed.), Medical devices: international perspectives on health and safety. Elsevier.

- WHO. (2010a). Financiamento dos Sistemas de Saúde - O caminho para a cobertura universal.

- MINSA. (2019). Melhoria dos Serviços da Saúde: “Não Deixar Ninguém para Trás.”

- Decreto Presidencial 260/10 de 19 de Novembro. Regime Jurídico de Gestão Hospitalar, (2010).

- Rowe, A. K., de Savigny, D., Lanata, C. F., & Victora, C. G. (2005). How can we achieve and maintain high-quality performance of health workers in low-resource settings? The Lancet, 366(9490), 1026–1035. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67028-6

- Dieleman, M., Gerretsen, B., & van der Wilt, G. J. (2009). Human resource management interventions to improve health workers’ performance in low and middle income countries: a realist review. Health Research Policy and Systems, 7(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-7-7

- World Health Organization. (2007). Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes: WHO’s Framework for Action.