| Original Article, Biomed Biopharm Res., 2023; 20(2):14-27 doi: 10.19277/bbr.20.2.324; PDF version [+]; Portuguese html [PT] |

Hydration patterns and beverage consumption among a sample of institutionalized senior adults in Portugal

Damião Clemente1, Diogo Sousa-Catita 2 ![]() , & Cíntia Ferreira-Pêgo 3

, & Cíntia Ferreira-Pêgo 3 ![]() ✉️

✉️

1 - School of Sciences and Health Technologies, Universidade Lusófona de Humanidades e Tecnologias, Av. Campo Grande 376, 1749-024 Lisbon, Portugal

2 - Residências Montepio – Serviços de Saúde, SA, Rua Julieta Ferrão nº 10–5º, 1600-131 Lisboa, Portugal

3 -CBIOS – Universidade Lusófona’s Research Center for Biosciences & Health Technologies, Campo Grande 376, 1749-024 Lisboa, Portugal

Abstract

Water plays an important role in different body functions, being fundamental for cells, tissues, and organs. It is also directly related to various processes, from maintaining body temperature to eliminating compounds. With age the feeling of thirst decreases, which can lead to inadequate consumption of water causing dehydration in the senior population. This dehydration can have consequences on the clinical status of this population, enhancing its clinical decline. The primary objective of the present study was to evaluate the daily consumption of liquid from beverages in institutionalized individuals in a senior adult residence in the Lisbon area. A cross-sectional observational quantitative study views. An adapted version of a specific fluid-validated questionnaire was used to assess the consumption of different beverages and total daily fluid intake. It was observed that institutionalized individuals did not consume enough total fluid intake to meet the European recommendations appropriate for their sex and age group. Nevertheless, individuals receiving artificial nutrition achieve a daily consumption of 1.5 liters of water.

Keywords: Fluid intake, water, beverages, institutionalized older adults, EFSA adequate intake

To Cite: Clemente, D. , Sousa-Catita, D., & Ferreira-Pêgo, C. (2023) Hydration Patterns and Beverage Consumption Among a Sample of Institutionalized senior adults in Portugal Biomedical and Biopharmaceutical Research, 20(2),14-27.

Author correspondence:

Received: 23/08/2023; Accepted: 7/12/2023

Introduction

Water is the largest body component (1), and it is directly related to several vital functions of cells, tissues, and organs, such as regulating functions, maintaining temperature, transferring different nutrients and other products, and eliminating compounds resulting from catabolism (2). As the human lifespan progresses, the relationship between hydration and health becomes increasingly complex, with particular nuances manifesting in the aging population. Advancements in our understanding of hydration in older individuals underscore the intricate challenges associated with aging, since hydration is of utmost importance in the senior population, and consequently, dehydration is a risk factor for this population (3). This dehydration can occur due to a loss of thirst (4), but also through losses like bleeding, vomiting, and diarrhea (5). The difficulty in maintaining hydration in older individuals may also be due to multiple other factors such as visual difficulties, swallowing problems (dysphagia), immobilization, intake of sedatives, or incontinence (3). Taking diuretics or other types of drugs can also be an aggravating factor as they cause a loss of body fluids (5). Dehydration can lead to the presence of headaches, xerostomia, temporary loss of sensibility and movement, fatigue, muscle weakness, dizziness, and in more severe cases, it can cause hypotension, tachycardia, or loss of consciousness, and even death (6). Low fluid intake is also associated with the worsening of pre-existing associated pathologies and a consequently decreased quality of life (1). Dehydration can be categorized in three different ways: a) isotonic, the most common, where the loss of water and ions are equivalent; b) hypertonic, a greater loss of water than ions; and c) hypotonic, a greater loss of ions than water (7).

The European Food Safety Agency (EFSA) recommends that the daily water intake from food and beverages in older adults should be 2 liters for males and 1.5 liters for females. Regarding the recommendations only from beverages, EFSA recommends the consumption of 1 to 1.5 liters of liquids for adult women and men, respectively (8). However, these recommendations do not take into account the health or disease conditions of the older adult. The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN), in turn, indicates that all older individuals entering a healthcare facility should be immediately considered at dehydration risk and be advised to consume at least 1.6 liters of fluid daily (9).

Older individuals and residents of extended care establishments, including residential care, long-term nursing care, and dementia care units, face heightened susceptibility to dehydration. This vulnerability arises from a higher likelihood of cognitive and physical impairments, hindering their capacity to recall and access beverages. A systematic review of 2015 (10) identified various interventions and exposures in effort to reduce dehydration in institutionalized older adults. However, the effectiveness of numerous strategies remains uncertain due to the prevalent risk of bias in many studies. Multifaceted approaches involving policymakers, management, and care giving personnel are the most probable means to mitigate the prevalence of dehydration in long-term care facilities. However, a more comprehensive exploration, utilizing robust study methodologies, is imperative to substantiate the efficacy of these strategies.

To address the pressing need for an enhanced evidence base in this domain, our study evaluates the daily consumption of liquids from different types of beverages in institutionalized individuals in the metropolitan area of Lisbon, Portugal. By contributing insights into the intricacies of water and beverage consumption in this specific demographic, our research aims to bridge existing gaps in the current state of art and to propel the discourse on optimal fluid management strategies, thereby promoting the well-being and longevity in the older adult population.

Materials and Methods

Design and study population

The present work consisted of a quantitative cross-sectional observational study. It was conducted in a Senior Residences Group consisting of four units in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area. The total sample included 350 participants of both sexes. The length of hospitalization varied according to the associated typology and the individual's rehabilitation needs. In these residences, various types of hospitalization were included: convalescence (staying institutionalized for 30 days), medium-term and rehabilitation (staying for 60 days), long-term and maintenance (staying for 90 days), and private institutionalized (variable institutionalization duration).

Anthropometric data

Patients who could maintain the orthostatic position were weighed using an automatic scale. Measurements were also made for the brachial and waist circumference using a tape measure.

In case, of mobility limitations anthropometric data was collected from evaluations previously carried out in these institutions. These measurements in Rabito's formula (11) allowed us to estimate the approximate body weight of the individuals who could not be weighed. However, it was important to check whether the patient had soft tissue increases in the upper and/or lower limbs, since this change may lead to errors in the measured values (overestimation of weight due to edema) and thus provide incorrect data that would condition the patient's treatment and evolution.

Fluid intake

Subsequently, participants were asked about their fluid consumption habits through the adaptation of a previously validated questionnaire (12). The questionnaire was adapted to the Portuguese language and to include only the beverages available in the institution. It was applied by the institution's trained Registered Dietitian in face-to-face interviews. The average water present in the enteral or parenteral nutrition supplements available in the units was recorded, as well as the 500 ml water bags given to participants receiving artificial nutrition. Participants who had communication difficulties or had some pathology that affected their memory/cognition were not questioned due to the possibility of the unreliability of the information obtained. However, family members were asked to make this data available for these individuals.

Ethics

The work was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Health Sciences and Technologies of the Universidade Lusófona (P13-22). The included participants agreed to participate willingly and answered the questions in person after signing the informed consent. For participants with pathologies affecting memory/cognition, signed informed consent was requested from family members/guardians.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis of the present study was performed using the statistical analysis program IBM® SPSS® Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated according to the international standards already established (13) taking into consideration the formula: Weight [kg]/Height2[m]. Two categories of age were designated (<65 vs. >65 years) for comparisons according to age groups. The normality of the variables was previously tested, and since they followed a normal distribution, parametric tests were used. The distribution of the variables was analyzed using ANOVA or t-student test, as appropriate. Results were presented as means (standard deviations, SD). Significant differences were considered as p-value<0.05.

Results

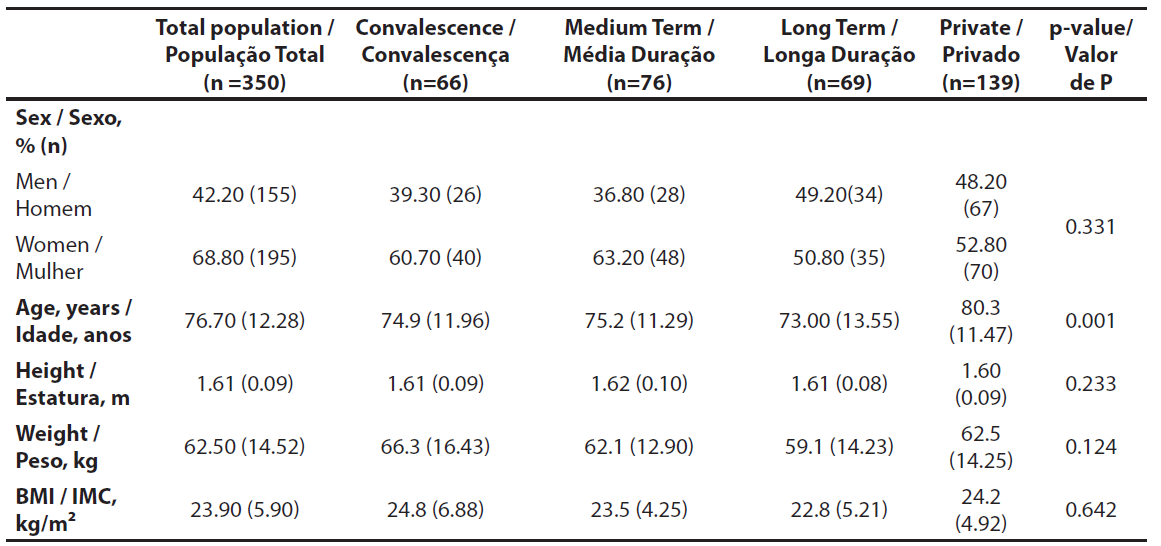

The total intake and different types of beverages consumed by 350 institutionalized individuals were analyzed. The general characteristics of the total study sample, which included 155 (44.2%) men and 195 (66.8%) women, can be observed in Table 1. The mean age was 76.7 ± 12.28 years. The BMI of the sample was 23.90 ± 5.90 kg/m2. Age was the only variable that showed significant differences (p<0.001) between the types of care, with individuals in the private sector older than the other groups.

| Table 1 - Sample characterization according to the type of institutionalization. |

|

| BMI: Body Mass Index. Comparisons were made with ANOVA tests, or student t-test, as appropriate, with a significance level of p<0.05. |

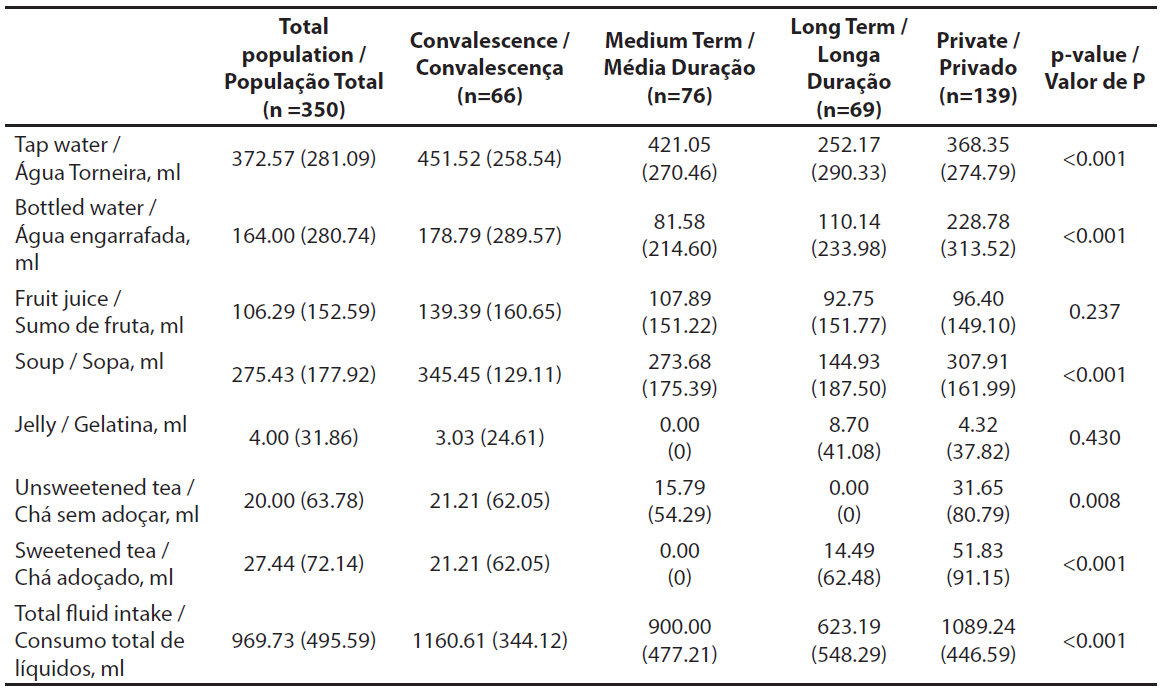

Regarding the fluid consumption according to the type of care, the average consumption of water (tap and bottled) was between 362.31 and 630.31 ml. The average total daily fluid intake for convalescent participants was 1160.61 ml, while that for medium -term participants was 900.00 ml. The average total daily fluid intake for long-term participants was 623.19 ml, and for private participants was 1089.24 ml. Significant differences between the analyzed groups in the consumption of water, bottled water, soup, unsweetened and sweetened tea, and total consumption were noted (Table 2).

| Table 2 - Fluid intake according to the type of institutionalization. |

|

| Comparisons were made with ANOVA tests, with a significance level of p<0.05. Data expressed as mean (SD). |

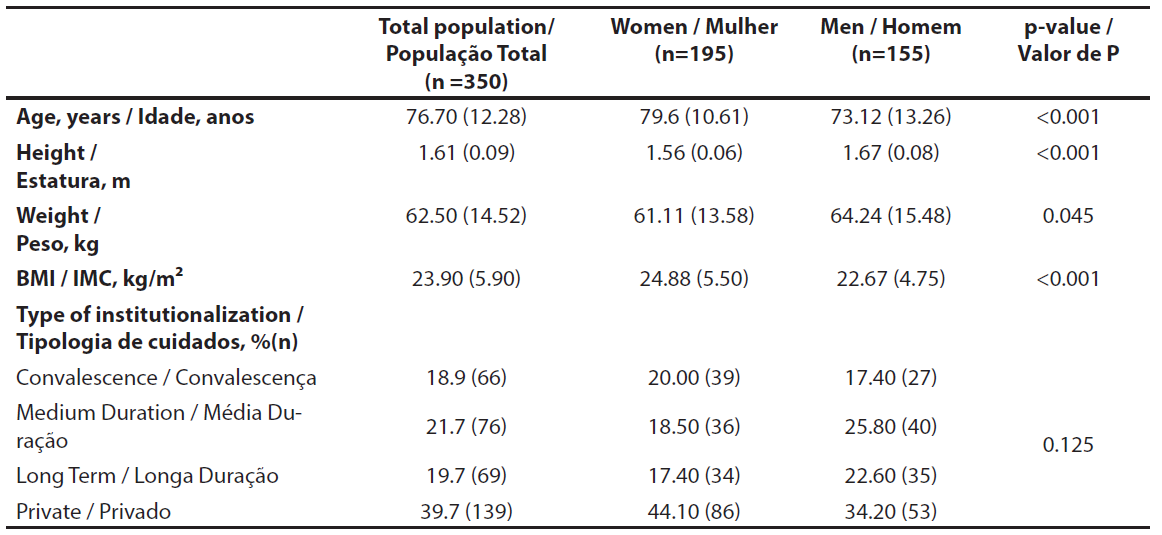

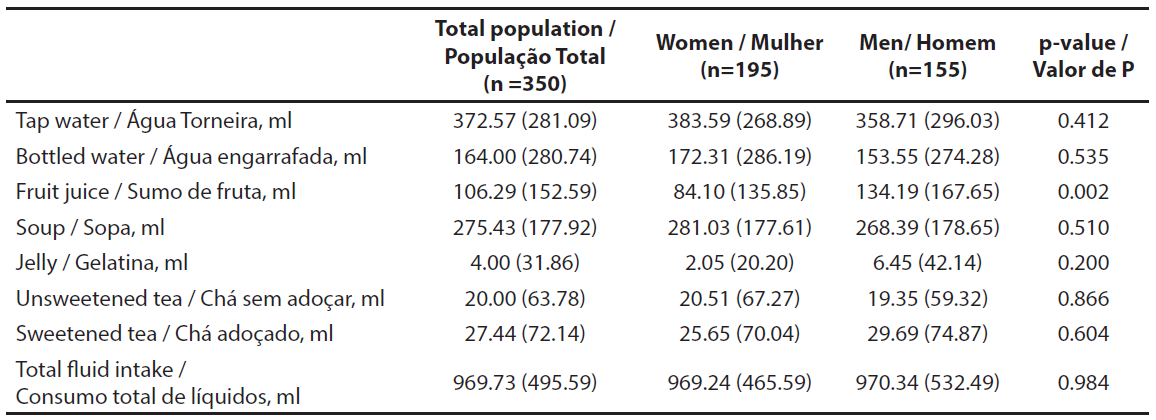

Analysis according to sex was also performed and age, weight, height, and BMI showed significant differences between the two groups analyzed, being men taller and heavier than women. On the other side, females were older and presented higher BMI values. These general characteristics according to sex can be observed in Table 3. Additionally, women presented a total daily intake of 969.24 ml and men of 970.34 ml, of which 559.9 ml and 512.26 ml were through the consumption of water (tap and bottled), respectively. Men showed significantly higher consumption of fruit juices compared to women (Table 4).

| Table 3 - Sample characterization according to sex. |

|

| BMI: Body Mass Index. Comparisons were made with ANOVA tests, with a significance level of p<0.05. |

| Table 4. Fluid intake according to sex. |

|

| Comparisons were made with ANOVA tests, with a significance level of p<0.05. Data expressed as mean (SD). |

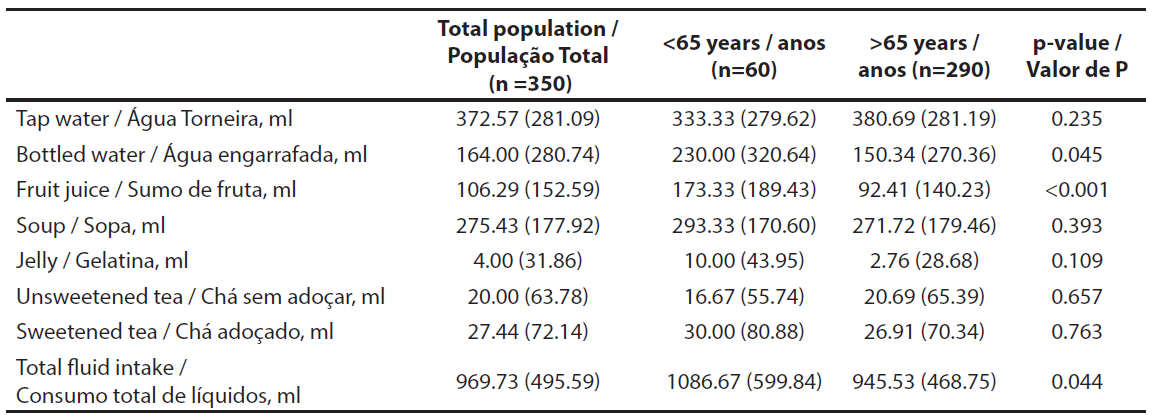

Table 5 shows the total daily fluid intake according to age categories (<65 vs. >65 years). The younger group presented a total liquid consumption of 1086.67 ml while the senior group presented an intake of 945.53 ml, of which 563.33 ml and 531.03 ml were through water (tap and bottled), respectively. Bottled water, fruit juice, and total fluid intake showed significant differences between the groups analyzed, presenting the younger group with higher consumption of these three types of beverages.

| Table 5 - Fluid intake according to age. |

|

| Comparisons were made with ANOVA tests, with a significance level of p<0.05. Data expressed as mean (SD). |

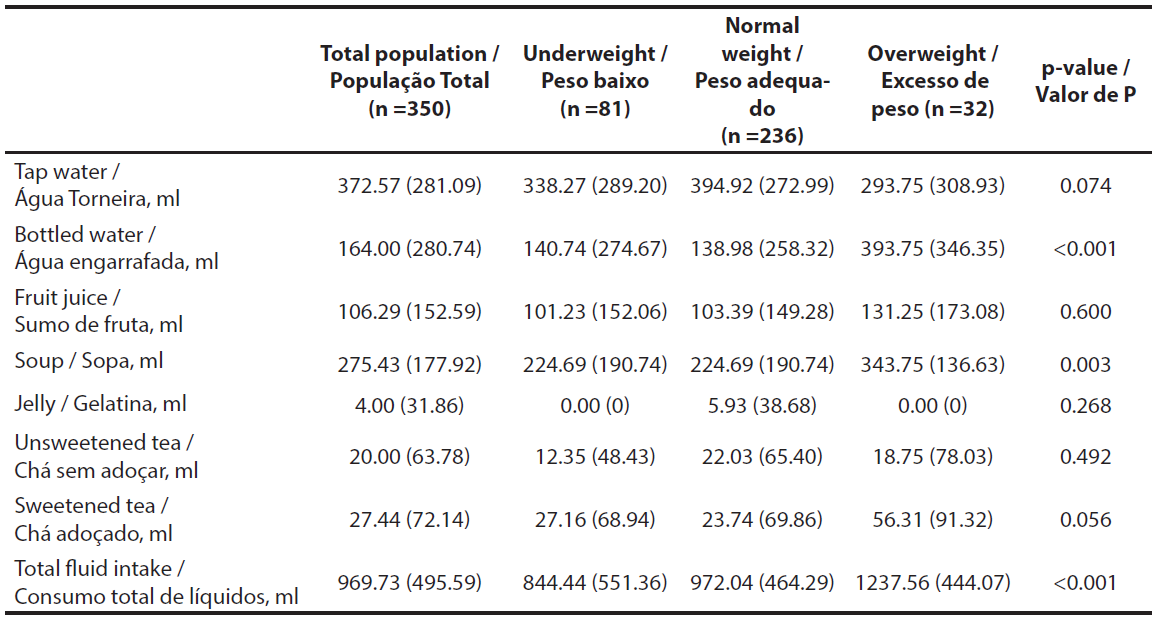

Regarding BMI categories, underweight individuals presented an average total fluid intake of 844.44 ml, adequate weight consumed 972.04 ml, and overweight 1237.56 ml (Table 6). Regarding water (tap and bottled), there was a consumption of 479.01 ml by the underweight, 533.9 ml by the adequate BMI category, and 687.5 ml by the overweight. Bottled water, soup, and total fluid intake showed significant differences, presenting overweight participants with higher consumption of these three types of beverages.

| Table 6 - Fluid intake according to BMI category. |

|

| BMI: Body Mass Index. Comparisons were made with ANOVA tests, with a significance level of p<0.05. Data expressed as mean (SD). |

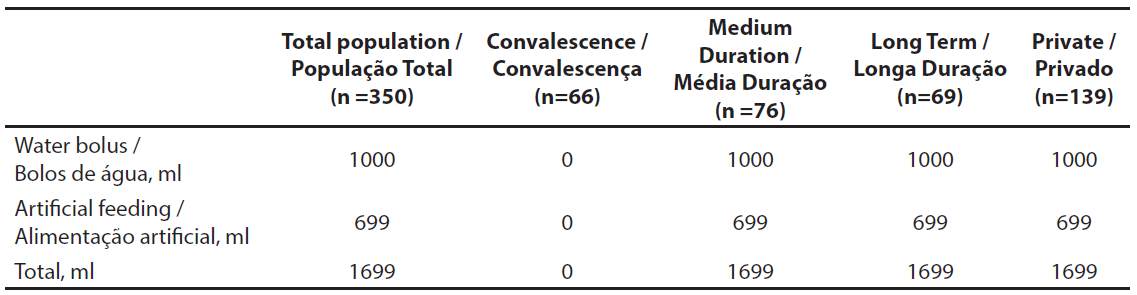

Finally, of the total sample, 44 participants received artificial nutrition (Table 7), either via nasogastric tube or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG). It was verified that the individuals received a total of two water bags, each with 500 ml, in addition to the nutrition supplements that already contained a water supply.

| Table 7 - Fluid intake for individuals with artificial nutrition. |

|

| Data expressed as mean. |

Discussion

The data collected in the present study seems to indicate that the institutionalized population showed a low daily consumption of liquids, presenting females with an average consumption of 969.24 ml and males with 970.34 ml, of which 559.9 ml and 512.26 ml through water consumption, respectively. Thus, it can be observed that, in general, this sample did not meet the European recommendations for their age groups and sexes, since the EFSA recommendations for adults and geriatric people, in terms of exclusive consumption of liquids, indicate that females should have an intake of 1000 ml and males 1500 ml (8).

The present results were also in line with the National Food and Physical Activity Survey (IAN-AF) for the years 2015 and 2016, where it was possible to verify that the Portuguese population usually consumed less than 1000 ml of water daily, with adults showing an average consumption of 956 ml/day and the senior population 780.1 ml/day (14). A previous study conducted in another senior Portuguese institution also examined the intrinsic behaviors of the population regarding their daily consumption of water and liquids. The data showed that 36% drank on average at least 1000 ml of water (15). These results indicate that the consumption of the institutionalised participants evaluated in this study seems to be similar, with an average consumption of 969.73 ml.

A reduction in mobility, as well as the presence of several pathologies, seems to be associated with a reduced desire to drink water and hypodipsia (16). The results bear this out, as convalescing people had a higher total consumption of liquids, and they stayed for only 30 days in their residences due to a temporary loss of autonomy. There may be several factors that influence low fluid intake by older individuals, especially when institutionalized. One of these factors may be related to the fear of urinating more frequently, especially related to the presence of movement difficulties (17). In the present study, it was observed that the older group presented a lower fluid intake compared to the younger adults. BMI, metabolic ratio, and body surface area have an impact on differentiating between obese and non-obese individuals regarding water consumption, with obese individuals having a higher consumption (18). In a study conducted in the United States of America, the authors concluded that there seems to exist a relationship between increased body weight and decreased water consumption (19). In the present study, however, the opposite was found. In the context of participants who were institutionalized and received artificial nutrition, our investigation revealed an average fluid consumption of 1700 ml. Adequate fluid intake is vital for essential nutritional support, and established guidelines suggest a range of 30 to 45 ml per kilogram of body weight. Given the average weight of the individuals in our study, the recommended fluid consumption should ideally fall between 1773 and 1989 ml. However, our findings indicate that the subjects did not meet the recommended fluid intake according to these guidelines. Inadequate fluid intake can have profound implications for patient health, potentially affecting hydration status, renal function, and overall well-being. This discrepancy between observed and recommended fluid intake raises concerns about the nutritional care provided to institutionalized individuals relying on artificial nutrition. Several studies have emphasized the importance of meeting prescribed nutritional requirements, including fluid intake, to optimize health outcomes in this vulnerable population (23, 24). Therefore, our findings not only underscore the existing gap in fluid management for these individuals but also emphasize the need for healthcare providers to tailor nutritional support more closely to established guidelines. Some of the strategies applied to increase fluid intake in the studied institution included the improvement of the interaction with participants by increasing their literacy about the importance of fluid intake. This provision of scientific information appropriate to the study population allowed them to learn useful ways to hydrate themselves, as well as educating them of the short and long-term consequences of a deficient intake. It is important to note that posters and flyers had already been distributed in different units as part of a health education initiative aimed at institutionalized individuals. Another strategy that was implemented involved filling individuals’ glasses or bottles and positioning them in easily accessible areas, facilitating increased fluid intake in various situations. While acknowledging the effectiveness of these strategies, future interventions should be conducted to further enhance nutritional literacy among institutionalized users and healthcare professionals responsible for their well-being, with a particular emphasis on the importance of adequate fluid consumption. A limitation of the study may be related to memory bias in providing the information. Another limitation comes from the fact that we used a questionnaire originally written in a non-Portuguese language and not adapted to the reality of the sample under study. Additionally, the cross-sectional design of the study does not allow the establishment of a cause-effect relationship. The strengths of this study are demonstrated by the comprehensive data collection involving individuals across different types of care and units, as well as the thorough evaluation of fluid intake among participants receiving enteral nutrition.

Conclusions

Institutionalized individuals in the analyzed private residencies from the Lisbon Metropolitan Area did not, in general, comply with the EFSA recommendations for water intake according to their age groups and sex. Nevertheless, individuals who received artificial nutrition and water bags were closer to these recommendations.

Authors Contributions Statement

D.S.-C.; C.F.-P., conceptualization and study design; D.S.-C.; D.C., experimental implementation; D.C.; C.F.-P., data analysis; D.C., drafting, editing and reviewing; D.C.; C.F.-P., figures and graphics; D.S.-C.; C.F.-P., supervision and final writing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by national funds through FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P. (Portugal), under the DOI 10.54499/UIDB/04567/2020 and DOI 10.54499/UIDP/04567/2020 projects. C.F-P. is funded by the FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P. (Portugal) Scientific Employment Stimulus contract [reference number DOI 10.54499/CEECINST/00147/2018/CP1498/CT0009).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all the participants and the institutions for the collaboration in data collection.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

1. Beck, A. M., Seemer, J., Knudsen, A. W., & Munk, T. (2021). Narrative review of low-intake dehydration in older adults. Nutrients, 13(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13093142

2. Jéquier, E., & Constant, F. (2010). Water as an essential nutrient: The physiological basis of hydration. European journal of clinical nutrition, 64(2), 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2009.111

3. Edmonds, C. J., Foglia, E., Booth, P., Fu, C. H. Y., & Gardner, M. (2021). Dehydration in older people: A systematic review of the effects of dehydration on health outcomes, healthcare costs and cognitive performance. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 95, 104380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2021.104380

4. Parkinson, E., Hooper, L., Fynn, J., Wilsher, S. H., Oladosu, T., Poland, F., Roberts, S., Van Hout, E., & Bunn, D. (2023). Low-intake dehydration prevalence in non-hospitalised older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland), 42(8), 1510–1520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2023.06.010

5. Volkert, D., Beck, A. M., Cederholm, T., Cruz-Jentoft, A., Hooper, L., Kiesswetter, E., Maggio, M., Raynaud-Simon, A., Sieber, C., Sobotka, L., van Asselt, D., Wirth, R., & Bischoff, S. C. (2022). ESPEN practical guideline: Clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics. Clinical Nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland), 41(4), 958–989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2022.01.024

6. Shaheen, N. A., Alqahtani, A. A., Assiri, H., Alkhodair, R., & Hussein, M. A. (2018). Public knowledge of dehydration and fluid intake practices: Variation by participants’ characteristics. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6252-5

7. Lacey, J., Corbett, J., Forni, L., Hooper, L., Hughes, F., Minto, G., Moss, C., Price, S., Whyte, G., Woodcock, T., Mythen, M., & Montgomery, H. (2019). A multidisciplinary consensus on dehydration: Definitions, diagnostic methods and clinical implications. Annals of Medicine, 51(3–4), 232–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2019.1628352

8. EFSA. (2010). How much water does my body need? The scientific answer from the European Food Safety Authority. EFBW Scientific Folio n°1, 1(1), 5–6.

9. Cederholm, T., Barazzoni, R., Austin, P., Ballmer, P., Biolo, G., Bischoff, S. C., Compher, C., Correia, I., Higashiguchi, T., Holst, M., Jensen, G. L., Malone, A., Muscaritoli, M., Nyulasi, I., Pirlich, M., Rothenberg, E., Schindler, K., Schneider, S. M., de van der Schueren, M. A. E., … Singer, P. (2017). ESPEN guidelines on definitions and terminology of clinical nutrition. Clinical Nutrition, 36(1), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2016.09.004

10. Bunn, D., Jimoh, F., Wilsher, S. H., & Hooper, L. (2015). Increasing Fluid Intake and Reducing Dehydration Risk in Older People Living in Long-Term Care: A Systematic Review. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 16(2), 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2014.10.016

11. Rabito, E. I., Vannucchi, G. B., Suen, V. M. M., Neto, L. L. C., & Marchini, J. S. (2006). Weight and height prediction of immobilized patients. Revista de Nutricao, 19(6), 655–661. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1415-52732006000600002

12. Ferreira-Pêgo, C., Nissensohn, M., Kavouras, S. A., Babio, N., Serra-Majem, L., Martín Águila, A., Mauromoustakos, A., Álvarez Pérez, J., & Salas-Salvadó, J. (2016). Beverage Intake Assessment Questionnaire: Relative Validity and Repeatability in a Spanish Population with Metabolic Syndrome from the PREDIMED-PLUS Study. Nutrients, 8(8), 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8080475

13. Garrow, J. S., & Webster, J. (1985). Quetelet’s index (W/H2) as a measure of fatness. International Journal of Obesity, 9(2), 147–153.

14. IAN-AF Relatorio Metodológico.pdf. https://www.ian-af.up.pt/sites/default/files/IAN-AF%20Relatorio%20Metodol%C3%B3gico.pdf

15. Dias, T. D. P. (2014). Hidratação em idosos Projeto “Água Viva!” ESTEsC.

16. Popkin, B., D’Anci, K., & Rosenberg, I. (2010). Water, hydration, and health. Nutrition reviews, 68(8), 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00304.x.Water

17. Robinson, S. B., & Rosher, R. B. (2002). Can a beverage cart help improve hydration? Geriatric Nursing (New York, N.Y.), 23(4), 208–211. https://doi.org/10.1067/mgn.2002.126967

18. O’Connell, B. N., Weinheimer, E. M., Martin, B. R., Weaver, C. M., & Campbell, W. W. (2011). Water turnover assessment in overweight adolescents. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 19(2), 292–297. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2010.225

19. Chang, T., Ravi, N., Plegue, M. A., Sonneville, K. R., & Davis, M. M. (2016). Inadequate Hydration, BMI, and Obesity Among US Adults: NHANES 2009-2012. Annals of family medicine, 14(4), 320–324. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1951

20. Medically Administered Nutrition and Hydration. (2020). Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing: JHPN: The Official Journal of the Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association, 22(3), E13–E16. https://doi.org/10.1097/NJH.0000000000000651

21. Schwartz, D. B., Barrocas, A., Annetta, M. G., Stratton, K., McGinnis, C., Hardy, G., Wong, T., Arenas, D., Turon-Findley, M. P., Kliger, R. G., Corkins, K. G., Mirtallo, J., Amagai, T., Guenter, P., & ASPEN International Clinical Ethics Position Paper Update Workgroup. (2021). Ethical Aspects of Artificially Administered Nutrition and Hydration: An ASPEN Position Paper. Nutrition in Clinical Practice: Official Publication of the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 36(2), 254–267. https://doi.org/10.1002/ncp.10633